Walking the Cooks River

Saturday 12th October

I met the Cooks River. Well, I met the main river. It’s many drains and canals and streams have made themselves known to me, but arriving at Tempe station to the rushing and wide waters of the river was an exciting moment – albeit a chilly, wet one as the unpredictable Sydney weather did its thing. Of course, ‘Swamp King’ as he has – reluctantly – allowed himself to be dubbed (note: King has been changed to Kin), Taylor Coyne, was my guide.

Me meeting the water I moved around the world for.

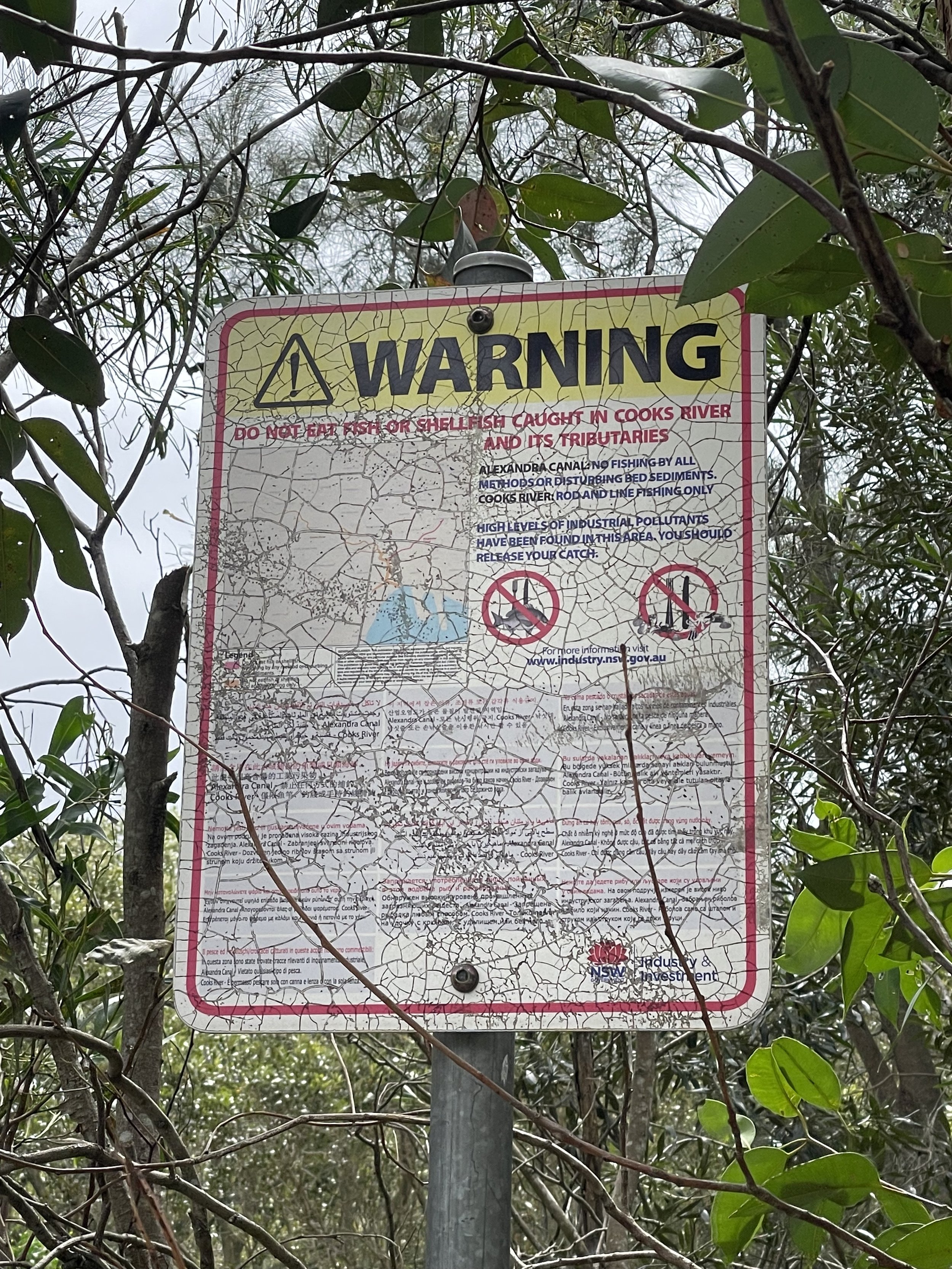

We begin at the station and work our way up the rivers banks, dodging cyclists and dog walkers, whilst keeping an eye out for the multitude of signage that dots its way around these public paths. A take away from these walks is the success and failure of so many of these public notices. The eye becomes immune to the attention-desiring announcements of various councils, public health boards, and community engagement groups. Half of them are illegible, ugly, or inaccessible. We pick them out as we walk, half-despairing-half-laughing at their inadequacy.

Two different signs, by different bodies, 4 metres apart, with the same illustration.

This river, especially this section, has a reputation. Taylor reflects, as we walk past the eroding steel structures that enforce the banks of the river, that the river carries narratives in its waters. A story of a working local population, struggling through hard times and working tirelessly. Industrial and resilient, but muddied by the overarching power of industry and pollution. As Leon Batchelor writes, “in 2008, an EPA briefing note warned anyone with development plans to beware of “the most severely contaminated canal in the Southern hemisphere””. Was this true? Is this river as toxic and doomed as these articles and narratives say?

“The story of the Cooks River is one of well-meaning destruction. Over two centuries, its wetlands and marshes have been beaten into a suburban drain, its water poisoned with industrial waste, its vegetation ripped up, and its banks lined with concrete and steel. It became an object of disgust and neglect; houses were built with their backs to it, with high fences to block the stench and floating garbage.” - Jordan Baker, Brook Mitchell (The Sydney Morning Herald)

Along the bank, we pass a fluffy, white, mop-like dog that runs towards us with bounding excitement. “River!” it’s owner shouts. I smile at Taylor – thrilled by the serendipity. Talking to “randomers” is one of my favourite pass-times and, within minutes, we are in a full blown discussion about the waters wellbeing. River’s Owner asks what we do and without thinking I say “river scientists”. Taylor scoffed (“You could have said we’re studying the river!” He howls later down the path, laughing at my inability to explain what I do). River’s Owner sighs, “this is a dying river. And if you love something you take care of it”. River – the dog – jumps at a passing poodle and she tugs him back off the path and onto the shrubby edges. I look out at an Ibis scratching under its wing, contorted and occupied. “All this funding and no action,” she continues, “for ten years I’ve walked up and down this path and no one’s done anything about it.” After ten minutes or so we part ways.

Taylor and I began to walk further upstream. “It’s interesting,” he reflects, “what she said isn’t necessarily true”. He gestures to two ibis on the far bank, turning their heads to submerge their beaks in the shallow waters. A red headed duck – I’m still learning names – passes them as we hear the guttural squawk of a crow, angry and red-sounding. There’s a disruption on the surface of the black water. A fish? An eel? Something I haven’t yet learnt the name of? The fingers of mangrove roots reach skywards, skimming litter debris, seemingly undeterred by its plastic-y presence. “We need to give them more credit. Why would they be here if it was so uninhabitable?”

In the past decade, bush care groups such as The Mudcarbs have worked to restore this river to a safe habitat for its mangroves and their inhabitants. The Cooks River Alliance is working to restore this place to a more acceptable state, with ongoing forums and discussions around ownership, and the steel barriers at its banks.

It seems that this body of water has been revered since before its reputation as a foul, and polluted place, “Europeans struggled with the unruly waterway. It had too many wetlands; it refused to behave like a European river,” (Baker and Mitchell) with each new generation attempting to tame it in some way or another, with the waters resisting in their eagerness to flood its surrounding areas. I come back to my earlier podcast about “impolite” wildlife, this is a body that will not co-operate. Not only this, but during a recent conversation with my friend and artist Brian Fuata, he reflected that it is not just about nature “reclaiming”, or even about restoring landscapes to their original state, but instead co-opting and co-becoming with the structures which have worked to control them. It rings true of the corroding steel barriers at the side of the river banks: though unseemly, ugly and often viewed as part of the problem, recent study has found that these barriers have in fact worked to hold and store pollutants which may otherwise enter our waterways. They have also become the home to thousands of oysters. I am reminded of the complexity of this work and the many human and more-than-human layers yet to uncover.

Plants of note:

- “She Oak” or casuarina trees, which are often found by the waters edge. Their pods deter snakes and their pines make for comfortable sleeping mats.

Ibis count x 10

Weird scary spider x 1